Pax Nortona – A Blog by Joel Sax

From the Land of the Lost Blunderbuss

Home - Health - Mental Illness - Addictions - The InterNet Argument Addict

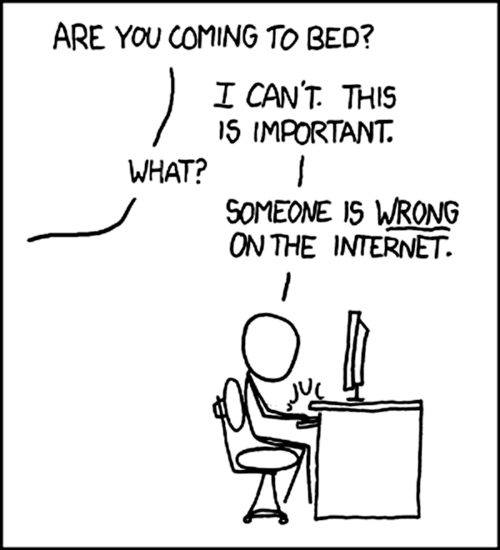

The InterNet Argument Addict

Posted on March 5, 2015 in Addictions Anger Frustration Mania Netiots

Difficult to end when I am feeling stable but energized and impossible when I am manic, InterNet disputes are a drug of choice for me. I just ended an exchange that went on for over an hour with someone on Facebook. She would not stop and neither would I. It seemed to me that no matter what I said to refute her, she kept repeating the same thing over and over. My ire was up: I had a defense to make and, equally important, someone to skewer. Then in the middle of it, I realized that I had become a Facebook Mr. Hyde, shared one last anecdote, and announced the end of my participation. Others have responded to the thread since then and I have not read what they said. Whether they indict me or stand up for me, I shall not involve myself anymore.

Difficult to end when I am feeling stable but energized and impossible when I am manic, InterNet disputes are a drug of choice for me. I just ended an exchange that went on for over an hour with someone on Facebook. She would not stop and neither would I. It seemed to me that no matter what I said to refute her, she kept repeating the same thing over and over. My ire was up: I had a defense to make and, equally important, someone to skewer. Then in the middle of it, I realized that I had become a Facebook Mr. Hyde, shared one last anecdote, and announced the end of my participation. Others have responded to the thread since then and I have not read what they said. Whether they indict me or stand up for me, I shall not involve myself anymore.

Long ago — on the abUSENET, I learned that it was a waste of time arguing against the trolls and cranks of the Net. If I spent a long time preparing an intelligent rebuttal to something they said, they’d dismiss it with a brute-force remark or lame witticism. Some even went so far as to create robots that would repeat the same argument every time certain key words appeared anywhere in the newsgroups. You could easily exhaust yourself fighting these. I gave it up for the Web because I realized that the newsgroups were a waste of time.

What part of the brain gets its heroin from such entanglements? What keeps me going? Scientists tell us that it has to do with our dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that deals with short term memory and decision-making. Put an InterNet virgin on a computer and in a couple of days, his brain will be flashing like he’d been there for ages. One critic of the Net believes that this destroys our ability to think deeply. And it has been demonstrated that the Net destroys our ability to engage in social situations. Speaking of the work of UCLA researcher Dr. Gary Small, a columnist for The Guardian writes:

Small is only too aware of what too much time spent online can do to other mental processes. Among the young people he calls digital natives (a term first coined by the US writer and educationalist Marc Prensky), he has repeatedly seen a lack of human contact skills – “maintaining eye contact, or noticing non-verbal cues in a conversation”. When he can, he does his best somehow to retrain them: “When I go to colleges and talk to students, I have them do one of our face-to-face human contact exercises: ‘Turn to someone next to you, preferably someone you don’t know, turn off your mobile device.’ One person talks and the other one listens, and maintains eye contact. That’s very powerful. One pair of kids started dating after they’d done it.”

He also fears that texting and instant messaging may already be dampening human creativity, because “we’re not thinking outside the box, by ourselves – we’re constantly vetting all our new ideas with our friends.” He warns that multitasking – surely the internet’s essential modus operandi – is “not an efficient way to do things: we make far more errors, and there’s a tendency to do things faster, but sloppier.” Of late, he has been working with big US corporations – Boeing is the latest example – on how they might get to grips with the effects of online saturation on their younger employees, and reacquaint them with the offline world.

But we are not powerless. If the brain is made aware of what is happening to it, it can save itself from this electronically induced narrowness. We are not prisoners of black box conditioning but free agents capable of making decisions for the better of our cognitive processes. In my case, I was able to take control of my passion and put a stop to the endless rounds of argument — of flame and counter-flame. What I did was get up from the computer, walk to a counter where I stood for several minutes looking at a French-English picture dictionary, and then check to make sure that we had the ingredients for dinner. Our power comes from our ability to make the conscious effort to control what we do at any given moment.

One thing I plan to do is watch that clock and live by it. No trying to win an argument as if it were a video game. The contest is always rigged by the fact that the other person probably is as enslaved by his dorsolateral prefrontal cortex as I am and unable to think about my points, just parrot the same thing he has been saying over and over. In the end it is not about winning, but about getting to sleep at a reasonable hour.