Pax Nortona – A Blog by Joel Sax

From the Land of the Lost Blunderbuss

Home - Spirituality and Being - Martyrdom Series - Martyrdom 7: Christ and the Cross

Martyrdom 7: Christ and the Cross

Posted on March 28, 2004 in Martyrdom Series Myths & Mysticism

Christ did not die for the white heron.

-W.B. Yeats

One of my best friends in college was Dan Davis, a fellow whose long brown hair and full beard led people to cross themselves whenever he entered a room. Dan was standing at the ice cream counter of a Thrifty Drug and Discount Store, waiting his turn, when another fellow walked up next to him. This stranger took a hard look at Dan. He rubbed his eyes. He looked again. Then he leaned over and whispered “You know: they’re going to crucify you.”

One of my best friends in college was Dan Davis, a fellow whose long brown hair and full beard led people to cross themselves whenever he entered a room. Dan was standing at the ice cream counter of a Thrifty Drug and Discount Store, waiting his turn, when another fellow walked up next to him. This stranger took a hard look at Dan. He rubbed his eyes. He looked again. Then he leaned over and whispered “You know: they’re going to crucify you.”

“Holy shit!” cried Dan. “Thanks for telling me, man! I’ll watch out for that!”

Christians around the world now study the calendar, counting the days until the beginning of Holy Week. They’ve learned all their lives to think of this as a clockwork where each event leads to the the overwhelming answer to the unstated question that God asks in the catechisms: What is going to happen? Jesus is going to die early in Passover. In the Phillipines, men work on putting holes through their hands so that they can be hammered to the crossbeams and raised to the skies on Good Friday. No Civil War reenactor allows the use of real bullets when he runs across the fields of Gettysburg for Pickett’s Charge. These people want the real thing: they do not feel complete unless they have felt the pain of Christ.

Most Holy Week celebrants go nowhere near as far as the Filipino victims; still, the week of services that begin with Palm Sunday and ramp up to the intense masses of Holy Thursday and the Stations of the Cross on Good Friday put the devout and the captives of Catholic academies and abbeys through an ordeal of aching muscles and other pains. Participants in this services believe that by enduring the hours spent indenting their knees and misaligning their vertebrae that they will come closer to Christ. Which is a sad recasting of the Crucifixion myth that leads believers away from the Sermon on the Mount and towards Stoicism. In the original myth, Christ didn’t die so that we might emulate his suffering: he suffered because we suffered.

Palestine was under a particularly bloody Roman occupation. To “keep the peace”, Pontius Pilate hauled up many “enemies of the state”. If you read the Gospels carefully, you will discover secrets for keeping your sanity under oppression. Hold on to your faith. Don’t put your stock in worldly things. Don’t make a public display of your religion like the quislings do: keep it close to your heart and perform your good deeds without thanks. When someone strikes you with the back of his hand, turn the other cheek so that on the rebound he has to treat you as an equal. Pay the damned taxes — they can’t take away what is truly precious.

The Romans sought to control a population by controlling its leadership. They relied on quislings to keep the masses in line. Think of the Sahedrin not as a Vatican of Jews, but as a front organization for the Roman occupation, so concerned about the worldly treasure of the Temple that they forgot about the faith. Several groups opposed the Sahedrin: one of them, the Pharisees, are the ancestors of today’s Jews.

The Romans sought to control a population by controlling its leadership. They relied on quislings to keep the masses in line. Think of the Sahedrin not as a Vatican of Jews, but as a front organization for the Roman occupation, so concerned about the worldly treasure of the Temple that they forgot about the faith. Several groups opposed the Sahedrin: one of them, the Pharisees, are the ancestors of today’s Jews.

Christ often spoke like a Pharisee and hung out with them. Pharisees spent much time in self-examination, checking their souls. To put them in a modern context, imagine a fellow who gets up in the morning, looks in the mirror, and says “Oh, you think you are such hot shit. But I know the truth about you. You’re hellbound, buddy. You’d rape your mother, murder your brother, prostitute your sister if you weren’t afraid of the law coming after you. You’re a hypocrite, mister, always making the public display and being rotten from just beneath the skinline to the marrow of your bone. Alas for you! Alas!”

One early group of Christian “heretics” were the Ebionites, Jews who remained beholden to the law. These regarded Christ as a great prophet sent by God to reform Judaism. Their favorite gospel? Matthew, the book that gave us the “blood libel”.

The Ebionite acceptance of the account of Jesus’s life which is most problematic for modern Jews isn’t so strange when you consider the larger Biblical context. The Bible tells again and again of times when the Chosen People let their God down. Yet, despite these incidents, God continues to love these people. In the context of Judaism, the Blood Libel is an illustration of human imperfection and peevishness. Think of Pharisees looking themselves in the mirror. “When God put everything on the line, when this good man showed us how to live, what did we do? We put Rome and greed before our faith. We hid or shouted what our occupiers wanted us to shout. We even were willing to give our sin to our children and those who had not been born — people who were totally innocent of our actions. Some lovers of God we are.”

Matthew, who wrote these words, had himself been something of a quisling by making his living as a Roman tax collector before leaving that life to follow Christ. In the context of Phariseeism and his own life, the Passion story serves to provoke his Jewish readers into scrutinizing their behavior. This is self-correction from the inside: like the jokes Jews and other groups tell about themselves, they are not meant for outsiders. When they do limp out of foreign mouths, however, they have a strange way of being twisted from instruments of humility into weapons of hatred.

The Ebionites distinguished themselves from other apostles and disciples of Christ by being Jews who did not believe in either the virgin birth or the resurrection. Christ was the latest and greatest of the prophets sent to God’s Chosen People. Like the Stations of the Cross, their crucifixion story ends with Christ being placed in the tomb owned by the Pharisee Joseph of Arimathea.

Other groups who believed in the divinity of Christ had different problems. First, there were what we now call the Adoptionists. These held that Christ had been born a mortal man, that he had lived an exemplary life, and as a reward for his goodness, he had been adopted as God’s Only Begotten Son.

Other groups who believed in the divinity of Christ had different problems. First, there were what we now call the Adoptionists. These held that Christ had been born a mortal man, that he had lived an exemplary life, and as a reward for his goodness, he had been adopted as God’s Only Begotten Son.

The other rival belief of importance were the Docetists who were often Gnostics. Docetists believed in the divinity of Christ from womb to sky burial. The idea of human beings killing a god troubled them. Middle East mythology, it was true, was rife with stories of dying and rising gods. Osiris, Baal, Inaana, Ishtar, and Persephone all descended into the lands of the dead and returned. In each case, however, their murder or abduction had been carried out by another god. The idea that the Romans — mere human beings who had an emperor who pretended to godhood — had executed the Messiah went against the Docetist’s concept of deity. Gods could not be harmed by men. So if Christ was the Son of God — a god himself — how did they explain the crucifixion?

Smoke and mirrors. Christ, said the Docetists, did not actually die on the cross. He only appeared to do so. The man who stilled the waters, healed the lepers, and drove demons out of their cranial palaces only appeared to walk among us, they argued. Think of Christ as a hologram, an energy field, an illusion that only appeared to be human and you have the image which the Docetists revered. Some went so far as to claim that Christ the Magician had switched places with Simon of Cyrene, the nice fellow who helped him carry the cross the last leg up Calvary.

Trickster Christ irritated other church fathers. The “deceivers…who do not acknowledge Jesus Christ as coming in the flesh” mentioned in 2 John 1:7 were the Docetists, followers of Simon Magus, a convert of Phillip who allegedly try to buy the powers of Jesus from Peter (see Acts 8:18-24). The Apostle John called the Docetists “antichrists”:

By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God;…He loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins. (1 John 4:2,10)

Emphatically, John preached that through Jesus, God had become flesh. There was no deception: God had allowed mere human beings to kill his earthly manifestation in Jesus Christ.

A doctor describes the suffering:

Hours of limitless pain, cycles of twisting, joint-rending cramps, intermittent partial asphyxiation, searing pain where tissue is torn from His lacerated back as He moves up and down against the rough timber. Then another agony begins…A terrible crushing pain deep in the chest as the pericardium slowly fills with serum and begins to compress the heart.

It is now almost over. The loss of tissue fluids has reached a critical level; the compressed heart is struggling to pump heavy, thick, sluggish blood into the tissue; the tortured lungs are making a frantic effort to gasp in small gulps of air. The markedly dehydrated tissues send their flood of stimuli to the brain…

Apparently to make doubly sure of death, the legionnaire drove his lance through the fifth interspace between the ribs, upward through the pericardium and into the heart. The 34th verse of the 19th chapter of the Gospel according to St. John reports: “And immediately there came out blood and water.” That is, there was an escape of water fluid from the sac surrounding the heart, giving postmortem evidence that Our Lord died not the usual crucifixion death by suffocation, but of heart failure (a broken heart) due to shock and constriction of the heart by fluid in the pericardium.

In 2002, the Diocese of Birmingham, England, shocked Christians around the world when it launched an ad campaign designed to appeal to nonbelievers in the 18 to 24 years of age range. “Body Piercing?” went one of the slogans that were displayed in Birmingham bus shelters. “Christ had his done 2000 years ago.”

In 2002, the Diocese of Birmingham, England, shocked Christians around the world when it launched an ad campaign designed to appeal to nonbelievers in the 18 to 24 years of age range. “Body Piercing?” went one of the slogans that were displayed in Birmingham bus shelters. “Christ had his done 2000 years ago.”

“The purpose of these posters is to try and grab the attention of a group of people with whom the church has lost contact” explained a Diocesan spokesman. A Christian Institute mouthpiece blustered that “The poster … trivializes the crucifixion of Jesus.”

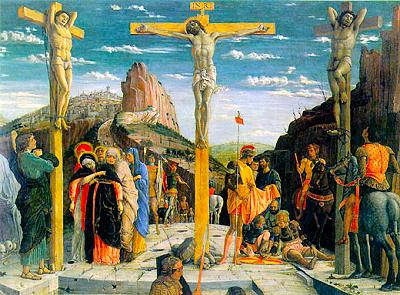

I raise this issue because the two poles of thought estrange us from the myth by suggesting that you can’t possibly measure up to Christ. The ad campaign focuses on coolness, the notion of Christ the Trendsetter, a Barbie doll who doesn’t lose it when the soldiers go about altering his body. Here Jesus led the way by being the first to receive the stigmata. This version of the myth reminds me of the crucifixion scenes which decorated the walls of the churches and the pages of catechism books as I grew up. In these depictions, Christ always appears in the middle. The nails are his alone. His two compatriots in death hang by their tied arms and legs. They suffocate: Christ is pierced and tortured.

These murals suggest that Christ, alone, received the tortures of the crown of thorns, the nails, the lashings, and the lance to his side. What the gospels give us is a very detailed description of this particular execution and no details at all of what was done to the other two men. It disturbs me to think how thoughtlessly Christian iconographers minimalized the suffering of the other two men as much as they could. The effect — whether intentional or not — raises the suffering of Jesus beyond what any run of the mill victim of Roman tyranny suffers and lends itself to a kind of neo-Docetism where the suffering of Christ takes on a form that is just not like anyone else’s.

Untold thousands suffered the Romans’ favorite execution-torture. The opposite of the Barbie Christian point of view, that of the Christian Institute where only the crucifixion of Christ and the apostles matter, trivializes the widespread barbarism of the Roman occupation. It’s not unlike singling out the occasional torturer for extradition while allowing hundreds or thousands of others to remain in the United States. It disturbs me because it blurs just what it was that made Rome so bad and makes it easier to blame the crucifixion — which was a routine execution — on the Jews of Jerusalem. This view underpins the misuse of Matthews account and the inversion of Pharisitical self-condemnation into the Blood Libel.

I side with John who, alone of the gospel chroniclers, details the steps of Christ’s murder: the most potent version of the myth holds that Christ became flesh, that Christ felt all that a human body could feel. Christ got corns on his feet. He suffered when everyone around him had a cold. When he walked from town to town, his legs hurt him: nothing felt better than having his feet washed in the shade of a friend’s garden. Yea, Christ ate and a few hours later, felt the discomfort of bowel movements. Like us, Christ crapped.

The human cry against God had been “Why do you put us through this kind of thing when you, yourself, have never suffered?” So, the myth of Jesus answers them: “I did. I was like you. I lived and had needs like you. When they nailed me to the tree, I cried because it hurt.”

Lacking in this version of Christ is the distancing from God that many attempt to press us against as template. This Jesus was no stoic. As the Apostle’s Creed puts it, he suffered, not uniquely, but mundanely. This Christ speaks to those in pain, those who are oppressed more truly, more compassionately than the Stoic or Neo-Docetist versions. Christ didn’t go through the Passion to one-up us, to make us mad at the Jews, or make us stop crying when cancer or a bullet ripped through our guts. The point is that God went through the human agony, to bring people closer to him.

Christ did not die for the white heron or to punish the Jews or to demand that we mutilate our bodies. Christ, the best of the myths protests, suffered and died because we suffer and die.